Medically Reviewed By Dr. Meghav Shah Updated on July 21, 2025

A Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) is a surgical procedure performed on patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) to improve blood flow to the heart, by rerouting around blocked arteries.

Coronary artery disease is characterized by a narrowing of the coronary arteries that supply the heart with oxygenated blood. This happens due to the buildup of cholesterol and other substances, collectively referred to as atheromatous plaque. The reduced blood supply to the heart can lead to chest pain, reduced heart function and a significantly higher risk for a heart attack.

After the severity of the disease has been determined through diagnostic tests like a Coronary Angiogram, CABG is recommended in cases where medication or coronary angioplasty isn’t feasible. Typically, it is the last line of intervention. A CABG is conducted by taking a healthy blood vessel from another part of the body — typically the legs, arms, chest or wrist — to make a new pathway for the flow of blood and oxygen to the heart — essentially bypassing the old, blocked pathway. This new pathway is called a graft.

The treatment of the narrowed arteries through a CABG enables better and smoother blood flow to the heart, which in turn positively affects all bodily functions.

CABG is primarily used to treat advanced coronary artery disease. The procedure typically addresses severe multi-vessel disease, especially triple-vessel disease (>70% narrowing in the three major coronary arteries) and left-main coronary stenosis (>50% narrowing). The heart has two main arteries–the right coronary artery (RCA) and left main coronary artery (LMCA) which in turn branches into two major vessels–the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX). When medical therapy or angioplasty (stents) provide insufficient relief, a CABG is suggested.

It also targets conditions like proximal left anterior descending artery disease combined with other blockages, especially in patients with diabetes and reduced left ventricular function.

As mentioned earlier, CABG is a later stage intervention. It can also be suggested to disable angina, despite optimal medications. Additionally, a CABG can be warranted in the case of failed percutaneous interventions or high-risk coronary anatomies which increase chances of heart attack or heart failure.

According to American Heart Association Journals Indications for Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Chronic Stable Angina

In most cases of advanced CAD, doctors have to decide between a CABG or angioplasty. As a general rule of thumb, CABG is preferred for more widespread and complex cases of CAD.

After coronary angiography, a SYNTAX score assesses the complexity of CAD. This score is usually an indicator for the type of intervention.

If your heart team has recommended a CABG, here’s what you can expect from the pre-operative stage through post-operative recovery:

Pre-operative Stage:

You will undergo various assessments that include blood tests, ECG, Echocardiogram and a coronary angiogram. Typically, an operation date is scheduled based on these results and potential outcomes. Two to three days before your surgery, you will be admitted and weaned off medication such as blood thinners (like Aspirin, Clopidogrel or Warfarin), in order to reduce bleeding risk. You may be given some gentle breathing exercises to strengthen your lungs.

The first step of the operation itself is anaesthesia monitoring, followed by invasive monitoring and intubation. Grafts such as the LIMA (Left Internal Mammary Artery) may be harvested endoscopically, while Heparin anticoagulants the blood.

CABG uses arterial and venous grafts for revascularization, however arterial grafts offer significantly better long-term patency. However, patient profile — history, comorbidities, vessel quality, age — will determine the choice of grafts. Here are some of the different types used:

Arterial Grafts: Modern CABGs are increasingly offering complete arterial revascularization. The LIMA-LAD graft offers 90-95% 10 year patency and survival benefit. Increased graft patency reduces the need for a repeat revascularization. The RIMA (Right Internal Mammary Artery) is suitable for other vessels, while the radial artery from the forearm works particularly well for distal targets. It offers an 80-90% 10 year-patency.

Venous Grafts: The Great Saphenous Vein from the leg remains the primary choice for venous grafts. The patency is at 70-80% for 1 year, but drops to 50% at 10 years. It’s harvested endoscopically, in order to minimize any leg complications.

Surgical Stage:

Choosing between on-pump or off-pump CABG depends on several factors. Patient history, a surgeon’s skill level and preference, and an assessment of the trade offs.

On-pump CABG drains the heart of blood, and provides a stable, motionless field for precise grafting. For years, this has been the gold standard of CABG, because it provides an ideal surgical environment which facilitates delicate work. This offers long-term graft patency.

Off-pump CABG is done on a beating heart, with the use of stabilizers. This reduces the complications associated with the CPB, in particular stroke and kidney problems. This is increasingly used in patients with a history of renal problems, severe lung disease or a history of stroke to reduce perioperative morbidity. The data on long-term outcomes is mixed. Clinical outcomes of on-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery - According to PubMed, show on-pump CABG has better long-term outcomes, however, some indicate that off-pump has comparable benefits. For some patients, off-pump CABG may even be the superior option.

Interestingly, off-pump CABG has seen higher adoption in India (>60% of cases), than North America (<15%). The reasons for this aren’t entirely clear, but off-pump CABG could be favoured due to its lower expenses. The absence of CPB reduces blood product use, equipment and ICU time, enabling smaller centers to offer competitive pricing. Additionally, trials conducted in India reported better early outcomes sustaining adoption.

As mentioned above, CABG has evolved into an umbrella term for bypass surgery, with multiple advancements offering different approaches, depending on the case. While a traditional median sternotomy remains the preferred approach for complex cases of multivessel disease and left-main disease, other approaches are offering quicker recovery times and shorter hospital stays with very comparable outcomes.

Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery-CABG (MICS-CABG):

Instead of opening the entire chest, by splitting the breastbone (sternotomy), surgeons make a small incision between the ribs (6-10 cm) on the left side of the chest.

Through this small opening, surgeons perform the bypass using specialized instruments. Usually, this approach involved a mix of arterial grafts — Left Internal Mammary Artery (LIMA) and Right Internal Mammary Artery (RIMA) — and venous grafts — Saphenous Vein Graft (SVG). However, complete arterial revascularization is more commonly being performed, offering higher graft patency.

A MICS-CABG is usually favoured for less complex cases or advanced cases. However, triple vessel disease and even advanced left-main disease is being treated via this approach. Aside from the patient profile, the key deciding factor here is surgeon training and skill.

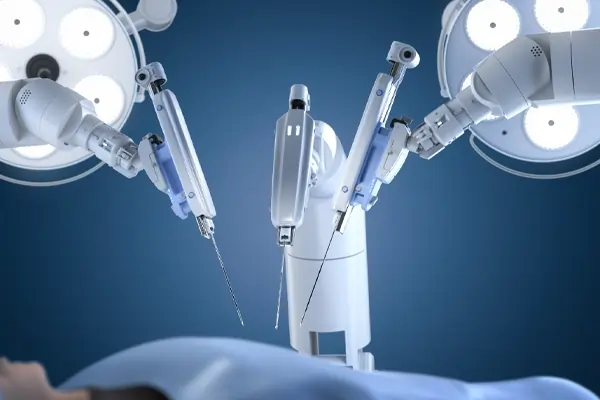

Robotic CABG:

Robotic CABG is a subset of MICS-CABG, which uses robotic systems like the Da Vinci to harvest grafts and perform the anastomoses, using precise, small incisions in the chest. The surgical instruments are mounted on robotic arms, and these arms are controlled by a surgeon who sits behind the console.

This innovation is gaining traction because the robotic arms filter any tremor that a surgeon may have. Additionally, the magnified, high-definition view of the heart provided by the console can enhance surgical precision.

However, this isn’t favoured for patients with complex coronary anatomies, extensive lung surgery, obesity, and any type of hemodynamic instability like ongoing acute MI (Myocardial Infarction) or Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump (IABP) dependence.

Indications to perform CABG are elective and emergency. Usually, it is recommended as a last line of intervention, in treating CAD after both medical therapy and angioplasty are no longer sufficient.

Left-Main coronary stenosis (>50%):

This is a very serious condition that usually requires a CABG. It indicates the narrowing of the left-main coronary artery, which is key to supplying a big part of the heart with blood. If unaddressed, it can lead to severe angina, heart attack or even death.

Triple-vessel disease:

When there are significant blockages in the three major coronary arteries, it is referred to as triple vessel disease. Patients with this condition face a significant risk of heart attack, and even death.

A blockage of 70% or more in any of these arteries is typically considered ‘serious’. An accurate risk profiling is conducted, before deciding on a course of treatment. However, CABG is usually recommended.

Double-vessel disease with proximal LAD:

Two vessel disease with the involvement of the proximal LAD (Left-Anterior Descending artery) is a pretty serious condition, as the LAD is key for blood flow to a big part of the heart.

The LAD runs along the front of the heart, and the part closest to the heart supplies a big area before splitting into smaller vessels. A highly diseased LAD can damage heart muscle or even lead to a heart attack.

Diabetes Mellitus with Multivessel Disease:

In heart patients, diabetes is a huge consideration in determining treatment. Diabetes can lead to silent myocardial ischemia (muted CAD), due to the gradual destruction of the autonomic nervous system. Patients can remain asymptomatic until a very advanced stage. CAD shows up in the form of a major adverse cardiac event.

Multiple studies have shown that CABG offers better outcomes than PCI (angioplasty). One of the important such studies was the FREEDOM trial. It showed that CABG lowered the risk of death, stroke or heart attack, compared to PCI, especially in diabetics.

Ischemic myocardium:

When there are large chunks of ischemic, viable heart muscle, a CABG can restore function to these areas, by bringing blood back to these areas.

Tests like stress echocardiography, cardiac MRI and PET scans allow doctors to understand if the heart muscle can heal (thus making it ‘viable’). If this is the case, a CABG can help improve heart function and lower other risks.

Failed angioplasty (PCI) or restonosis:

When PCI fails or is not viable, CABG is the most viable option. While angioplasty is used commonly, there are certain coronary anatomies that don’t make it a favourable intervention. In these cases, CABG offers a more reliable and lasting solution.

PCI techniques continue to improve vastly, however complex lesions — long, calcified or hard-to-reach lesions — are still a challenge for PCI. Additionally, high-risk placements such an ostial left-main block could make stent-delivery and placement very difficult.

In such cases, CABG can offer a long-term solution, reducing the need for repeated procedures. In addition to these, high risk coronary syndromes are a huge reason for CABG. If a patient is having an acute heart attack (MI), an emergency angiography is done to diagnose the condition of the occluded arteries. However, the choice to do a CABG depends on many high-risk factors. Timing after a heart attack is key too. If the heart is too stressed and other complications present, a CABG may be scheduled for a later date. However, if there’s high-levels of ischemia and a huge risk of more problems, an early CABG is recommended.

Cardiogenic shock from left-main stenosis, triple vessel disease or post MI-ventricular dysfunction unresponsive to support prompts an emergency CABG. A failed PCI or angiographic accident, ischemia unresponsive to medical therapy (including IABP) can also warrant immediate surgery.

The most important test in understanding blockage placement and coronary anatomy is the coronary angiography. The angiography helps determine a SYNTAX score, which in turn helps doctors decide between PCI and CABG. An echocardiogram measures ejection fraction and ventricular function. ECG detects arrhythmia and ischemia. Blood tests check other markers like glucose and lipid levels, kidney and liver function, coagulation and CRP levels.

Additionally, chest x-rays evaluate lung and heart size, stress testing identifies ischemia unresponsive to medication. Carotid ultrasound and CT brain may precede with stroke-prone patients. Pulmonary function and carotid doppler tests screen for other comorbidities in higher-risk cases.

Tests are conducted at regular intervals pre-operation to understand how a patient’s overall cardiac health is doing. Based on these tests, a more advanced risk stratification is offered. Tools like the STS risk calculator and EuroSCORE II offer personalized risk profiles, which predict chances of post-operative bleeding, duration of hospital stay, intra-operative mortality, 30-day mortality, morbidity, and long-term outcomes. While many of these tools are being continually refined, they add clarity in the decision making process and help patients and their families understand the risks involved.

High risk patients (STS > 8% or EuroSCORE II > 5%) face elevated mortality (5-20%) prompting hear-team review, off-pump considerations or partial PCI revascularization alternatives. Lower risk patients (STS <2%) suit robotic and minimally invasive approaches. Sometimes, despite a high risk level, doctors opt for a CABG, as survival chances outweigh mortality risks.

Recovery after a bypass surgery happens in phases, rehabilitation plays a key role in healing and protecting your heart.

Phase 1: In-hospital (Day 1-7):

You will stay in the ICU for 1-2 days, and a couple more days in the hospital. Nurses and physiotherapists will help you sit up, breathe deeply and take short walks to regain strength.

Phase 2: Early outpatient (2-6 weeks):

At home, recovery continues with gradual return to light activities. Wounds are checked, stitches removed and pain reduces steadily. During this phase, many patients begin cardiac rehabilitation — supervised sessions with light walking, slow cycling on a stationary bike, stretching and relaxation exercises to improve stamina and confidence. The recommended aerobic exercise intensity is 150 mins/week, during this phase.

Long term (after 6 weeks):

Most patients are able to get back to their normal routines. Those who stick with a full cardiac rehab program do much better — research shows consistent rehab can reduce the risk of mortality by nearly 50%, compared to partial participation. Rehab would include a heart-friendly diet, regular aerobic exercises like brisk walking or swimming, stress management and quitting smoking if needed. With time, most patients regain strength and a better quality of life.

We usually advise patients to undergo 36 sessions (12 weeks) of focused cardiac rehab. In some cases, we may advise as many as 72 sessions.

Like any surgical procedure, CABG carries risks. While there are some generalized risks, the outcomes vary largely from patient to patient.

Generalized risks include:

In-Hospital Complications of Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery in Patients Older Than 70 Years - According to PubMed. Elderly patients (>75 years), diabetics, those with prior stroke, low ejection fraction, renal disease or emergency status face significantly higher odds of complications. Renal failure requiring dialysis is often considered the comorbidity that raises CABG mortality the most.

Undergoing a CABG can be a very mentally and emotionally overwhelming process. In elective cases, it’s necessary to have complete clarity of the procedure and potential outcomes. Oftentimes, patients and their families are left second-guessing their decisions.

Here are some useful questions to ask:

1. Which is the better option–median sternotomy or MICS-CABG–and why?

2. Will it be an off-pump or on-pump CABG?

3. How many grafts will I need, and which arteries will be treated?

4. In my specific case, what are the risks and how do they compare to the average risk?

5. How do you measure the risk levels? Can I have a personalized risk profile for second opinions and reference?

6. Have you treated patients with a similar case profile? What were the outcomes?

7. Why was I recommended for bypass surgery and not angioplasty?

8. If I choose not to have surgery, what are my options? And, what are the possible outcomes?

9. Can I reschedule my surgery? If so, what’s a safe timeline?

10. What is the expected recovery time, in my case? When can I return to work, exercise or daily activities?

11. What should I AVOID after the surgery?

12. What long-term changes will protect the success of my bypass?

13. What are the chances of a repeat bypass?

Selecting the right surgeon is the most important part of your bypass journey. Make sure you take the time to arrive at a decision you and your family are comfortable with.

Try to look for a surgeon who has specific experience with the type of procedure recommended for you. Ask how many similar surgeries they perform each year, and their success rate. The expertise of the surgeon plays a huge role in selecting an approach — some may prefer a sternotomy for complex multi-vessel disease, however another may be comfortable with a minimally invasive approach.

Converse openly with potential surgeons, to understand their approaches. A good surgeon will take the time to explain your options, discuss risks honestly and answer your questions clearly.

While the surgeon and surgical team are the most crucial aspects, the hospital infrastructure is very important. Typically, look for a super-speciality hospital that conducts a high-volume of CABG surgeries. While multispeciality hospitals sometimes offer CABG surgeries, super-speciality hospitals are best equipped for complex CABGs, robotic and minimally invasive approaches and redo bypasses.